All by my selfie

After an apprenticeship with the photographer Kurt Blum, Balthasar Burkhard was hired at the end of the 1960s as the official documentary photographer of the Kunsthalle Bern. Photographing the exhibitions gave him the chance to view many artists who would go on to influence his own artistic orientation. From the minimalist and conceptual works, he retained characteristics such as seriality, the use of raw materials and the physical apprehension of space for his own photographic work. In 1974 he travelled to the United States where he held his first solo exhibition. In this series, he provides a reading of the body based on selected and disproportionately enlarged details. Back in Switzerland, from the 1980s onwards, he began to adopt the form of the large-format polyptych in order to magnify essence. Some of his 8 and 13 metre long female nudes are spread over several panels, as in the exhibition at the Kunsthalle in Basel in 1983. His monumental photographs favour a tight, frontal composition, as in the series Bamboos (1990-1991) photographed in an objective, life-size manner with minimal staging. Captured from a helicopter, his visions of metropolises (1997-1998) - Mexico City, London, Los Angeles, Tokyo - show the density and violence of urban life. Shot in Mexico City on the same theme, Balthasar Burkhard's film Ciudad, projected on three screens, was presented at the Musée d'art moderne et contemporain in Geneva in 1999.

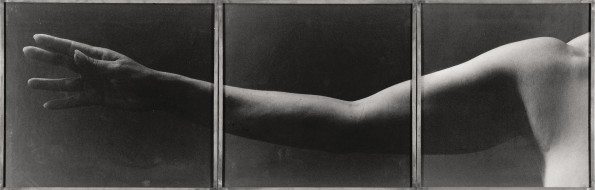

Baltasar Burkhard’s work is a triptych of an arm unfolding. The hand seems outstretched, allowing an opening up on the left side of the frame. The forearm, gently bent at the elbow gives a sense of impulse to the image’s composition like a sort of harmonious curve, an intermediary between the two edges. The shoulder, where the light is concentrated, marks the starting point of the arm’s ascent , of it’s span that renders it almost disproportionate. The use of black and white reveals the beauty of the image through an objectivity which tames and transforms it. It is thus that the image escapes the confines of its own reality ( but not it’s truth), as the manifestation of some fantastical vision. It has been magnified in order to better see, in order to better appreciate what beauty remains once a body has been dismembered, what isolated detail. This is a reversal of the relationship between the object and its observer. Everything exists on the scale that the artist freely gives it in spite of all reason, playing on vertigo, on ambiguity, on the fringes of what can be white or black, with a large place left to grey. The reality revealed to us is double, multiple, and the image, true to its essence, plays tricks on us. Caught in the trap of the lens and therefore of objectivity, the object defends itself, seeks out ways out to reach other angles than those usually proposed to the eye. Burkhard's work questions the relationship between man and nature, the epicenter of which lies in the mystery of the origin of Creation. Despite its intrinsic symbolism, the work also aims to stimulate the viewer's sensitivity. The initial distance between the audience and the work is eroded to make way for a sense of proximity and appropriation of what is nevertheless foreign and inaccessible. An intimate encounter takes place, a dialogue between the viewer and the viewed, despite the strong objective power of the motives.

Frac Provence-Alpes-Côte d’Azur, 2015