Asian Spring

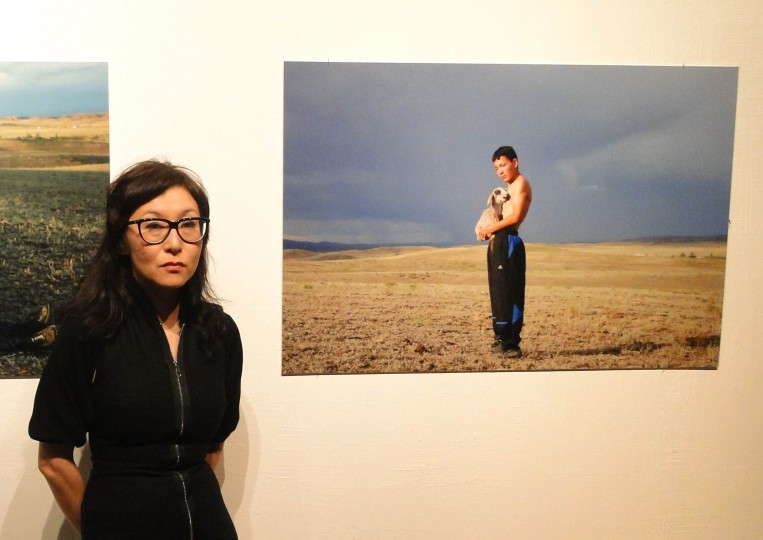

Originally from Kazakhstan, Almagul Menlibayeva splits her time between Berlin and Almaty. Her signature aesthetic, in which photographs and videos are combined, takes on a post-Soviet nomadic form, that of contemporary Kazakhstan, following her initial training at the school of futurism of the Soviet avant-garde. In what she calls “her archaic atavism,” an almost mystical anthropomorphism, she explores the collective unconscious of the populations of the Central Asian steppes between the Baikonur Caspian Sea and the Altai.

After 80 years of Soviet control and the ravages of cultural genocide, her work signifies the revival of an ancient voice: after a long period of neglect, the eternal song of the tribes resurrects the celestial gods and the myths of Mongolia. In her recent photography series, Almagul reveals a terrible report denouncing the moral and environmental consequences of the drying of the Aral Sea. Her shocking images, almost mythological in scope, constitute overwhelming proof of the environmental disaster.

Indeed, the Aral Sea, a saltwater lake between Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, which was once the 4th largest lake in the world, was methodically drained, causing one of the most important environmental catastrophes of the 20th century. The diversion of the rivers fed the intensive cultivation of cotton in Uzbekistan and the rice fields in the desert of Kazakhstan. These gradual punctures first caused salinisation, then evaporation and the progressive drying up of the lake, leading to the disappearance of indigenous species and the pollution of soils with fertilizers, pesticides and insecticides. The poisoning has caused rates of cancer, anemia and tuberculosis in the region to explode, not to mention the appalling increase of infant mortality and the experimentation and storage of biological weapons by Russia, the future consequences of which are still unknown. Almagul uses the desolate scenery of these barren desert shores to revive gods and goddesses of a lost past, the last hopes of a people and nature that have been scorned and desecrated.

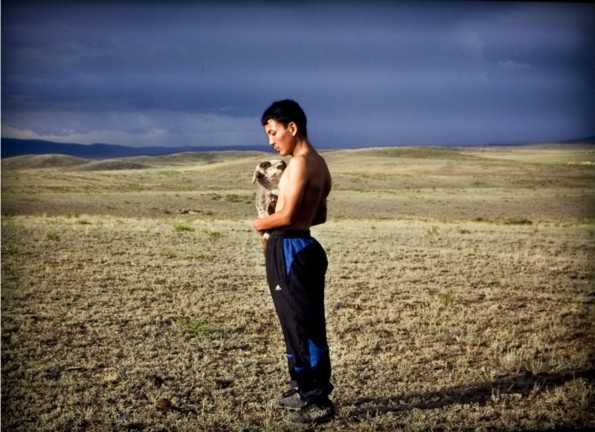

In images of profound simplicity, she embodies the desolate ruins of a fallen steppe empire where the grass no longer grows, and recalls the abandonment of its nomadic populations sacrificed to the oppression of communism, the uprooting of its values, civil wars, the greed of men and natural disasters. To revive these lands of exile, Menlibayeva embodies them in the form of fantastical creatures, hybrid four-legged centaurs, daughters of wolves or red foxes, horned beasts cradling lambs.

Stranded mermaids guard in vain beached wrecks on poisoned shores, a derisory Titanic, eaten away by rust and salt, now deprived of a future of sailing and glory, immobilised under a burning sun. A fictitious frozen army of virgin soldiers awaits an invisible and volatile enemy, which could be called gas or radiation, and watches over the young dead who appear to sleep, without a blanket or a shroud, like soldiers or fallen sinners. In this lifeless universe, however, sharp irony and ridicule also appear, with scenes reminiscent of tourist brochures or the erotic-chic kitch imagery of arms trade fairs.

Most importantly, Almagul renews, in a poetic and sensual way, the shamanism that has survived Communism and Islam. She appeals to the supreme god of Central Asia and the Turkish pantheon, Tengri, who controls the celestial sphere, all creations and rebirths. She portrays him as an innocent young man who carries a lamb in a steppe with a clear horizon and no borders. To give him a voice, she becomes a shaman, those messengers whose souls leave the body in a state of ecstasy, serving the spirits, protecting the members of their tribe from misfortune, finding the missing, uncovering the causes of diseases and discovering the cures, reading the future in sheep’s bones, driving away evil spirits.

Her status as an artist implicitly allows her to assume this role of healer and to take on the forms necessary for this renewal. She becomes the regenerative mirror of the world of these sacrificed animals, the architect of temples to be rebuilt, open to the winds, between the Muslim worlds, the great achievements of the ancients, the traditional yurts and colourful ribbons that in their twists and turns recall the old Silk Roads. She recreates the cohesion of these nomadic peoples and shows the path being forged for a possible future.

She has made a visual and poetic contract with the spirit of the Taiga, the rivers to which she intends to return the waves, and the great blue sky in order to appease the wrath of nature, after man has so viciously desecrated it. She is the link between the world of the visible and the invisible, of the present, the past and the future which, in her work, are in constant communication.

Véronique Maxé