L'Energie des Matériaux

Mario Merz grew up in Turin and attended the University of Turin’s army faculty for two years. During the Second World War, he joined the anti-fascist Justice and Liberty group and in 1945 he was arrested and imprisoned for distributing leaflets. In prison, he drew any and all subjects, from morning to evening, never wavering from his chosen medium. When he was released he rediscovered the Turin hills, where he recorded the grass, the sun, the scents and the noises as a seismograph. With the tip of a pencil, he traced the convolutions of his surroundings. It’s a kind endless cycle of perceiving and drawing. He shapes a language that will shape the world.

After the Liberation, encouraged by the critic Luciano Pistoli, he dedicated himself to painting full-time and began to practise oil painting.

He began with an expressionist-abstract style of art, then moved on to a more informal approach (subverting the creative rules rather than trying to overcome them). He held his first solo exhibition in 1954, at the La Bussola Gallery in Turin. In the mid-sixties, he abandoned painting to experiment with materials such as neon tubes, with which he pierced the surface of the canvases to symbolise an infusion of energy. This was also his first experiment with three-dimensional creations, or "volumetric paintings".

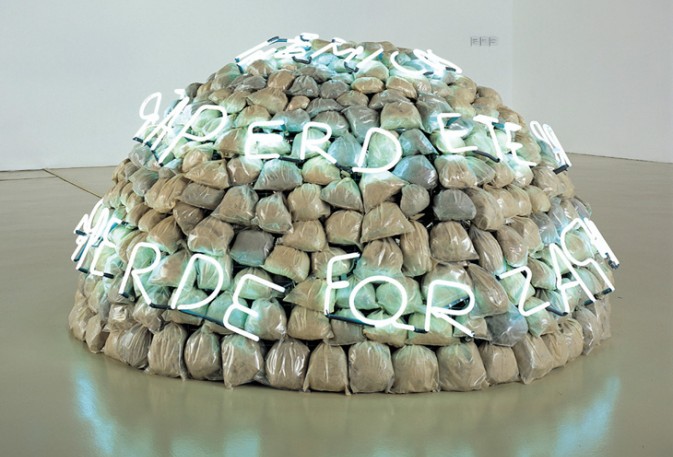

He attended the first displays of Arte Povera with the artists who participated in the collective exhibition organised by Germano Celant at Galerie la Bertesca de Genoa (1967). Merz, Michelangelo Pistoletto, Giuseppe Penone, Luciano Fabro, Alighero Boetti and others later reunited at the Gian Enzo Sperone Gallery in Turin. It quickly became one of the group’s hallmark moments. The climate of 1968 and the charge of political and social renewal are evident in his works, in which he began to use neon lights to recreate protest slogans from the student movement.

From 1968 he began to create archetypal structures such as his ‘Igloos’, made using contrasting materials (including glass, earth, and lead) which have since become characteristic of his work and which represented the artist’s definitive split from the confines of the two-dimensional frame and plan.

In 1970 he introduced the Fibonacci sequence into his work, a symbol of the inherent energy of matter and organic growth. He achieved this either by placing neon numbers in his work or elsewhere in the exhibition space - as he did in 1971 along the spiral viewing ramp of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, on the Mole Antonelliana in Turin in 1984, and on the Manica Lunga of the Castello di Rivoli in 1990.

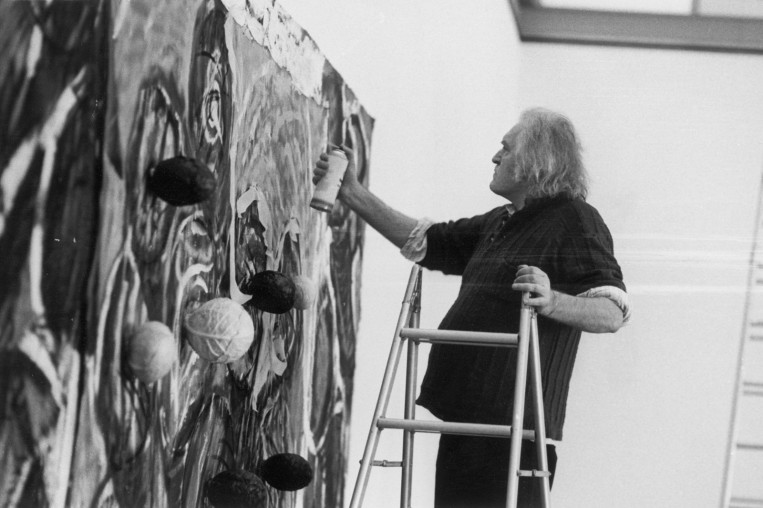

In 1976 he began to incorporate the symbolic figure of the spiral into his work, which was successively associated with the figure of the table, on the surface of which he placed fruit or vegetables so that, left to their natural destiny, they introduced the dimension of real time into the work.

At the end of the 1970s, Merz returned to figurative art, drawing large images of archaic animals, which he defined as prehistoric, on large unframed canvases.